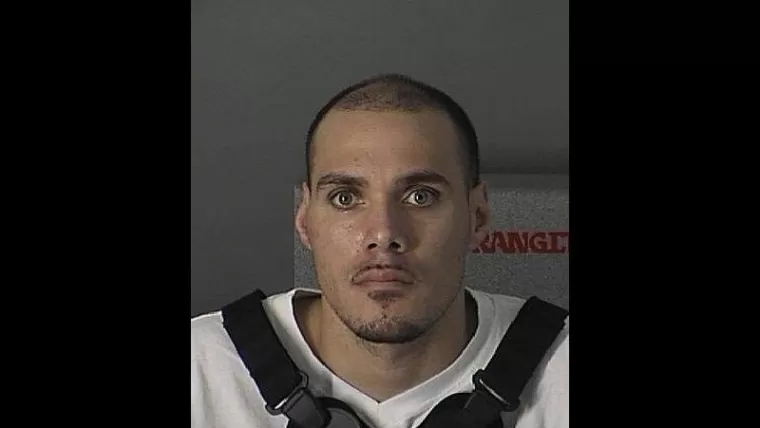

Kreshae Humphrey, 26, bathes her daughter, Nevaeh Soto De Jesus, 3, inside of a baby bath tub in the middle of their living room. The parents bathe all three of their girls with bottled water because they believe the children were sickened by the tap water at the Southern Comfort mobile home park off U.S. 19 in Clearwater. The family is suing the park’s owner over the issue, but the owner and the state say there are no problems with the drinking water there. [MARTHA ASENCIO-RHINE | Times]

CLEARWATER — At Southern Comfort mobile home park, residents knew not to drink the water. The taps can run brown and smell like the toilet. On other days the water stung from too much chlorine.

Parents watched as their children developed skin lesions and lost their hair. Families kept cases of bottled water piled in their kitchens, to drink and cook and wash with.

Southern Comfort was all they could afford. Many residents were undocumented. Some feared the repercussions of speaking up. Others say they did complain — but were ignored.

The owners of the park operated a small sewage treatment plant on-site that leaked bacteria and feces into the groundwater. The Florida Department of Environmental Protection spent a decade trying to get the owner to fix those problems. But the owner gave up.

A judge has now ordered the park closed. Everyone must be out by Oct. 31.

Once, nearly 500 residents lived there. About a dozen families are left, scrambling to find a new place to live.

Yet in all the years they spent living there, state officials never tested the tap water in their homes for bacteria. They say the wastewater system did not poison the drinking water and that they followed the law in addressing the situation.

Baby Erica’s skin, though, is soft and clear. The 5-month-old has never touched the tap water. Her mother only bathes her with bottled water and baby wipes. That’s how she bathes all her girls now.

Humphrey’s family and another family are suing Southern Comfort Park Inc., claiming they were exposed to “unsafe” and “unsanitary” water. They accuse the mobile home park of sickening their children and robbing them of their homes.

The mobile home park owner’s attorney, J. Allen Bobo, denied the lawsuit’s allegations and said the park has never had a problem with its drinking water. He also said the owner is out of options.

“We have no choice but to shut the property down,” Bobo said. “We can’t make it work.”

• • •

Humphrey and Eric Soto De Jesus, 26, moved into Southern Comfort at 24479 U.S. 19 N about three years ago, as they were starting their family.

Tucked away from the usual sprawl of U.S. 19’s storage units, strip malls and car dealerships, the park felt like an oasis. The streets were lined with rickety retro homes decorated with flower patches on the front lawn. The couple remodeled their home and built an extra bedroom.

Down the street, on the other side of a gate covered in overgrown plants, is a concrete rectangle a little bigger than a hot tub. It is the park’s on-site wastewater treatment facility.

vThe homes there are connected to an old system of underground septic tanks. But as the tanks failed over the years, the park diverted wastewater to its treatment facility, according to state records, sometimes illegally.

The muck was supposed to be processed to remove bacteria and floating waste — like toilet paper, feces and other bits that came down the drain. The treated wastewater would then be released underground.

State records show infractions that go as far back as 1972.

“A review of our permit files indicate the facility has had a history of problems …. but adequate improvements were never completed,” wrote one regulator in 1986. They worried the contaminated wastewater could be flowing into Old Tampa Bay.

In 2010, the Department of Environmental Protection sued the owner in Pinellas-Pasco Circuit Court to bring the plant up to standards.

In the lawsuit, the state said the amount of waste and bacteria in the wastewater was too high and the equipment was poorly maintained. Excess rags covered aeration tanks while grease and floating feces coated the clarifier. The facility also allowed untreated or partially-treated sewage to overflow, saturating the drainfield with dirty water.

That sewage could have leaked into the surrounding environment, experts say. The park’s drinking water comes from a well — a source vulnerable to groundwater contamination.

Nevaeh was impatient to get in the tub, then impatient to get out. After she climbed out, she tried to dip her feet back in the water. Then she wanted to squeeze the tubes of ointments her mother had waiting to soothe her rash.

Humphrey slathered the girl with Aquaphor, Hydrocortisone and a steroid cream, then zipped her back in her onesie to keep her moisturized, and stop her scratching. The bottled-water baths started in April, and while the two older girls are starting to heal, it is a struggle to keep them from scratching themselves raw.

“I won’t let my babies touch the water,” the mother said of what comes out of her faucets.

Humphrey’s neighbors, Josefina Charrez Pedraza, 39, and Jorge Torres, 40, said their family only cooks with bottled water. They had to buy prescription creams to cure the itchy rashes her boys, ages 7, 15 and 17, suffered. Their family also sued Southern Comfort.

Grace Fullford, 62, said her family uses bottled water to brush their teeth and wash their faces. They usually bathe in the water, but they don’t trust it. When the water runs particularly dirty, she said they skip bathing for days.

Her son, 41, has suffered recurring infections from MRSA — antibiotic-resistant staph bacteria — that recently required surgery.

“I don’t know whether it’s the water,” she said. “But I tell him ‘Don’t get that water on your skin.’ ”

Bernardo Camargo Hidalgo, 49, said his wake-up call came seven years ago when his children’s hair started falling out. He spent nearly $500 to install a water filter for his mobile home.

“I saw my kids brushing their teeth with that water, and I was brushing mine with it, too, and it smelled so terrible,” he said. “I just thought — we just can’t live like this.”

After he got the filter, he said their hair stopped falling out.

For many at Southern Comfort, dealing with dirty tap water was better than facing the county’s punishing housing market. Over the years, the park had filled up with families from Mexico and Central America. They focused on work and tried not to call attention to themselves.

Adolfo Pérez’s parents spent $50 a week buying enough bottled water for their family of four. They overlooked the water problem because they had more pressing needs, he said, such as work, rent and food.

“Do you know the word conformismo?” said Pérez, 22, as his family piled mattresses into the back of a truck, preparing to move out. “It means that you’ll settle for what is happening around you. You won’t demand more. I think that’s what we are seeing around here.”

His family found a more expensive house in Pinellas Park. Pérez said he will be relieved to leave the water problems behind them, and the feeling of powerlessness.

“The owners know they have an advantage,” he said. “I think it’s not fair that this happened in a country where we all have the same rights.”

• • •

Southern Comfort Park Inc.’s attorney said the mobile home park’s managers never received any complaints about the drinking water.

The attorney, Bobo, said the families’ lawsuits confuse the sewage water system with the drinking water system.

“The drinking water is completely different than the sewer system,” he said. “Whatever test required by the DEP have been done, and we have never had a problem with the (drinking) water.”

The state also told the Times its records show no contamination of Southern Comfort’s drinking water. The owner hired a certified lab to test monthly water samples at multiple points in the distribution line. They found bacteria once, in 2018, which was deemed a “false positive,” said Department of Environmental Protection spokesperson Shannon Herbon. In subsequent tests, no bacteria was found.

“The compliance issues at Southern Comfort are entirely related to wastewater, which is not in any way connected to the drinking water,” she said.

Issues with the color and smell could be the result of iron and sulphur in the water. That would have no impact on public health, she said, and doesn’t violate federal water standards.

But the families’ attorney, Gil Sanchez, said there is a link between the sewage issue and the drinking water and they intend to prove that in court.

“We will show a jury they knew what was happening and turned a blind eye,” he said.

Experts say that even if no contamination was found in the well’s drinking water, old pipes and dirty groundwater could still create a toxic mix.

“It may test fine at the source, but by the time it gets to the users, it may be contaminated,” said Joseph Petersen, the director of Agriculture and Environmental Sciences at Florida Gateway College, after reviewing the lawsuit’s complaint for the Times.

When a wastewater treatment facility is outdated and hasn’t been properly inspected, he said, it can leach bacteria and harmful components back into the aquifer and the wells.

One way to determine if the drinking water is contaminated would be to regularly test the water coming out of the taps, experts said. The state said it conducted tests in several different areas around the park, but not from residents’ taps.

The state said it informed Pinellas County about the problems at Southern Comfort. But Pinellas Department of Environmental Protection Division Director Kelli Levy said her department first learned about the sewage issue in 2017, when a resident complained to the agency about the drinking water.

The county tested a creek behind the park, which drains into Alligator Lake and feeds into Tampa Bay. Levy said the levels of bacteria, such as E. Coli and fecal coliform, were “off the charts.” The park owner was fined $17,508.

“Honestly, when we got out there and saw the conditions,” Levy said, “we were quite shocked that this had been going on for so long.”

Her department, though, only has jurisdiction over the creek — not the drinking water.

But if the creek were contaminated, experts say it could affect the tap water, too.

• • •

Humphrey remembers the day she learned they were all going to lose their homes. It was early April, right before she had Erica. Her mother-in-law, who lived in a mobile home across from hers, came running across the lawn.

“Do you know we have to leave?” she said, waving a letter from management.

“This must be a joke,” was all Humphrey could think.

For Southern Comfort’s residents, it was like they were being punished a second time.

Families who had lived in the park for years were suddenly thrust into the county’s booming housing market. Rents for apartments or houses cost double or triple what they paid monthly at Southern Comfort.

They’ll also lose the thousands they’ve spent to buy and fix up their homes. The residents say their homes are too old to move and could fall apart in the process — and they can’t afford that option anyway.

Their only compensation will come from the Florida Mobile Home Relocation Corporation’s fund. Single-wide owners can get $1,375 and multisection owners $2,750. The park’s owner will have to reimburse the state for those payments.

Humphrey and Soto De Jesus don’t know where they’ll go next.

The family was paying $658 per month to rent the land under their mobile home. The prices they saw online for apartments are eye popping: nothing under $1,000. And everything requires a deposit — which they can’t afford because Soto De Jesus lost his full-time sales job soon after they learned the park was closing. He’s looking for a new job and works part-time to keep the family afloat.

They qualified for Section 8 housing support and the Pinellas County Housing Authority bumped Southern Comfort residents to the top of the list because of the imminent closure. But Humphrey hasn’t found anything for a family of five with a newborn.

Their options are dwindling. Their relatives can’t take in the children. They’ve heard that there are homeless shelters that take in families, but then they’ll have to leave all their possessions behind.

“We don’t want to go there,” she said. “We don’t want to live on the street with our kids.”

Staff photographer Martha Asencio-Rhine and senior news researcher Caryn Baird contributed to this report.